Why I'm leaving Twitter (and you should too)

I woke up this morning, grabbed a cup of coffee, sat on my porch, and decided to leave Twitter. The idea is to first lock down my account without deleting it (for archiving purposes), and eventually, once I mirror my tweets elsewhere, I’ll delete my account for good.

I’ve been thinking about it for a while, but more frequently after Musk’s acquisition started to take effect. Then recent events affected me enough to write this manifesto and take action.

Dan Luu being unable to post a link to his Mastodon profile.

Paul Graham’s account being suspended for mentioning the Mastodon.

Twitter’s confirmation that all mentions to Mastodon (and other social medias) are henceforth forbidden.

As a social network, Twitter has more than served its purpose. For years it’s been my go-to place to learn from incredibly interesting individuals outside meatspace after I curated my feed and found my people.

And these people are the reason I’m writing this post today. (By the way, if you’re reading this, you’re most likely one of them.) Since I don’t want to lose contact with the dear friends I made over there, I won’t leave without setting forth my arguments and trying to persuade a few to follow me.

Here are some of the reasons I think Twitter and all other centralized social networking services are doomed to fail, why we should seek a better home, and why this home should be Mastodon.

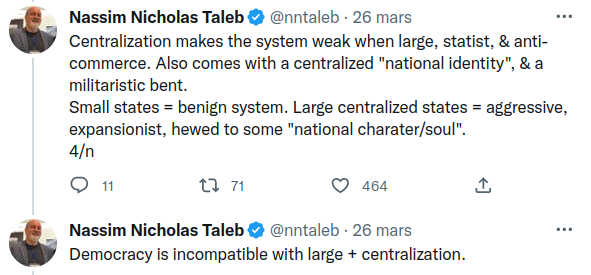

Centralization is neither good or bad, but bad centralization is awful

If Twitter was a country, it would be a world superpower that had been run for decades by an inflated government that never truly understood its people and their needs. But despite the bad management, the country just worked. Unless you promoted illegal content or spewed hateful rants or downright lies that could damage society at large, you were free to write whatever you wanted. One wouldn’t even remember that there was a government, which is a good sign for a country whose pitch is freedom to speak up.

Then, out of the blue, a rich outsider buys that country, lays off half the government’s staff, and turns that superpower into a diplomatic joke, the playground for an eccentric billionaire turned internet troll who sports a severe narcissistic disorder and a very dubious sense of justice.

Francis Fukuyama once wrote that authoritarian regimes are neither good or bad. A good authoritarian regime, in fact, wouldn’t be that different from a democratic one. You’d still get to vote. Journalists would still have free speech. Everything government-related might even be more efficient since less people in charge means less friction and shorter response times.

The problem is when bad leaders take over with no checks and balances or a lever to remove them from power if things go awry. Fukuyama calls this the “Bad Emperor Problem”. A reminder why authoritarianism is never the answer.

What we have on Twitter now is a set of arbitrary rules that is most definitely not in its public’s best interest. Criticizing the CEO or reminding others about the existence of alternative social networking sites shouldn’t be a reason for anyone to be cast out, especially because of its consequences. A suspension means being deprived of reaching out to all your friends still on the network.

“Oh, but I’m safe, Musk would never notice me. There are bigger fishes out there.” Can you really be sure? It began with journalists, then comedians, then critics, then common people who mentioned other social media. Never underestimate a bored ruler with absolute power.

Mastodon, on the other hand, could never become an authoritarian regime nor bargain with your ability to communicate with friends because Mastodon isn’t ruled by one person or company. It’s not a country, but a network of scattered city-states that get to choose which other cities they maintain contact with.

If a city-state turned evil, either because its dwellers became toxic or because a nutjob dictator bought his way into power, the neighboring cities are free to cut off the bad apple from the network. And the probability of a city-state going bad in the long run is always non-null.

But the biggest advantage of decentralization for us, the city dwellers, is that we are not hostages of a bad ruler’s whims. If we lived in that now spoiled city-state, we’d be able to leave and move to a place of our choice without losing contact with the rest of the world. We can even bring our stuff along with us, which means that all messages and contacts will remain intact in the process.

The concept of decentralized web services may sound weird nowadays, but email providers have been working in a decentralized fashion for decades. With your Gmail account, you can write to anyone who signed up for Hotmail or Yahoo! Mail. In the case that Gmail goes bad, you can sign up for an email account elsewhere and keep emailing grandma cute memes.

A sense of community

Besides decentralization and the advantages that come with it, the other reason that made me opt for Mastodon is the heightened sense of community.

The hardware that keeps Mastodon afloat is not owned by millionaire corporations. Instance admins are quite often normal people who lend some of the CPU power in their basement to host a Mastodon instance free of charge. With that in mind, instance users volunteer or donate spontaneously, especially after the huge influx of new users in recent months. Kris Nóva, the admin behind the hachyderm.io instance, which I chose to call home, saw her user base jump from a few hundreds to more than 30,000 in a span of a couple of months. She said in an interview: “I am surprised at how willingly people began donating.”

It’s not hard to hear about spontaneous manifestations of altruism on Mastodon. And it still baffles me years after my first contact with the network.

I don’t know why such behavior emerges more easily in some online communities than others. Maybe it has to do with the kind of people that the decentralization concept tends to attract. For example, there are some groups of users who promote assemblies where every user in the instance can participate and decide what’s best for the server. This is the case on social.coop, an instance that looks to me like the birth of an actual solar punk community. I don’t know about you, but hearing something like this warms my heart.

The recent events on Twitter have been an opportunity for me to rethink the future of centralized web services. By abiding to their nature, we get convenience in the expense of agency, and become subject to a board of directors’ (or director’s) wills. They can limit your account for petty reasons (like Twitter), build a paywall (like Medium), or keep non-registered users out (like Instagram), and you have to either deal with it or face ostracism.

The same can happen to decentralized networks like Mastodon, but at least you can refuse the local authority’s terms without leaving its users behind. And believe me: once you know them, you won’t want to leave them behind.

My Mastodon profile: @brunoarine@hachyderm.io