Something is better than nothing

I started having therapy sessions in 2016, and it was one of my best decisions in all adulthood. I had decided to seek help because I wanted to put an end to my chronic anxiety, social phobia, impostor syndrome, and self-esteem issues. And above all, I wanted to do away with the uncomfortable and persistent feeling that I was hostage to my own emotions and thoughts.

But despite all these pressing concerns, I remember that my first session’s ice breaker was a completely different subject, which I deemed way less important: how commonly I left projects halfway through.

As an example, I told my therapist about the science blog I tended to during my college years. It was called “Nebulosa Nerd’s Bar”. I loved writing on it, and I carried on the habit of publishing one post per week until I had 1000 people subscribed to my newsletter. Suddenly it started to feel more like a chore than a hobby, and I stopped writing it outright. As with every personal project I’ve ever had, I stopped caring before I could reap the long-term benefits of it.

A few months of therapy in, and my therapist suggested me to try meditation.

When I turned 30, I began to question things I had never questioned before. The meaning of everything. How to tackle moral dilemmas. Whether it’s wrong to lie for the greater good. What is right and wrong anyway. Whether I should have a job that causes a positive impact in the world, or get a job that is not so dignified but that pays well so I could donate part of the money to charity. Our choices as adults. Our place in the Cosmos.

I plunged into the works of Western and Eastern philosophers. I came to know more about Epictetus, Epicurus, Plato, Nietzsche, Confucius, and Laozi. They all had interesting insights on life, but I didn’t find a definitive, absolute answer to my questions.

Nevertheless, during my searches I stumbled upon a book called Zen Wrapped in Karma Dipped in Chocolate, which contained some funny yet witty remarks about life, based in the precepts of a Buddhist doctrine called Dzogchen. Here’s an excerpt from it:

“The best way of life is to live the way you want to. But living the life you really want to live is not the same as living the life you think you want to live. If you don’t know the difference, you very well might be better off living the life everybody else thinks you should. […] Before you can live the life you truly want to live, you need to find out what you truly want. That takes patience. You need to look straight into your own mind and weed out your real desires from the false ones you’ve created out of thought. I only know of one way to do that, and you should have figured out by now what that is. Yep. You got it. Lots of zazen.”

Meditation, huh?

At the same time that adulthood gave me raise to moral dilemmas, I was also afflicted by health problems such as hormonal dysfunctions, high blood sugar, joint pain and—worst of all—an inability to focus.

Joint pain is treated with a good workout routine and ice packs. Glycemia with a few tablets of Glifage 500 mg XR after meals. As for lack of concentration, there is no allopathic drug as of yet.1

When I said that to the doctor, she suggested meditation.

It was just a matter of time until I gave in to peer pressure and started meditating.

But meditation has always made me skeptical. For starters, I read that there are a dozen different ways to meditate. Which one to choose? Do they all promote the same benefits? What are the benefits anyway? Why am I looking up about it anyway?

Following the suggestion of the rationalist community on Less Wrong, I decided to take the steps described in The Mind Illuminated: A Complete Meditation Guide Integrating Buddhist Wisdom and Brain Science, authored by neuroscientist John Yates.

Since then, it’s been almost two years since the first time I sat down to meditate in the morning. It’s also been two years since I’ve been able to maintain the habit for more than three mornings in a row.

But as the saying goes, “something is better than nothing.”

I heard the sentence above from a mindfulness instructor who was hired by the company to give us employees a series of stress management lectures. (Which, I must confess, I was pretty skeptical at first.)

“Something is better than nothing.”

That expression made me persist at meditation. I would sit down and close my eyes even when I didn’t have more than 5 minutes to spare before leaving to work. It would be enough to meditate a little because, after all, there was no scoreboard.

And in one of those few meditation sessions, it clicked.

In Yates’ book, it is said that meditation is an end in itself. There is no goal, only the process. Or rather, the process is the goal. Just like love or happiness, the more you pursue the goal, the farther it gets from you. What if writing works the same way? What if writing is a kind of meditation?

Writing, or rather the dynamics of writing, has a proven therapeutic potential. If an activity is pleasant, and neither too easy nor too difficult, it is possible to enter a kind of trance that psychologists call a flow state. Craftsmen feel it. Musicians feel it. Programmers feel this. (Except you, VisualBasic programmers. Sorry.)

I felt this flow when writing before. Writing became a burden because I created unrealistic expectations: I should have fun while I wrote; the people who read what I wrote, on the other hand, should have fun too; my old college friends should be with me on this project. The harshest of realities is that there is no magic tablet anywhere in the Universe saying that anything has duties. There’s no guarantee that I should have fun exactly like I used to. Nothing guarantees that my readers will all appreciate what I write. There is no guarantee that going back in time is possible.

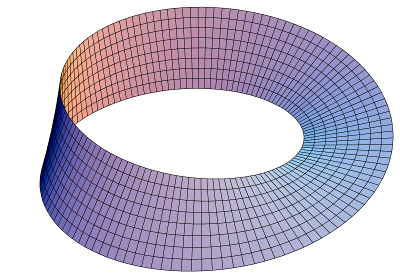

Creating goals in terms of things that are out of your control and suffering for not achieving them is illogical. I placed myself in a big Möbius ring, a non-Euclidean mental labyrinth that gave no sign that I was heading towards the finish line. From the moment I got distracted with elusive goals at the expense of relaxing and enjoying the ride, keeping a blog (or the comics) became a little personal hell.

What if I could write again just for the pleasure of writing? Just to relieve intracranial pressure from time to time; to purge the moral dilemmas that are piling up?

If I could learn anything from my therapist, it’s that we should—or rather, prefer—to opt for strategies that make us more functional individuals. Functional for whatever your utility function values most. If “enjoying the journey over the destination” is something that is within my control, and if it would somehow help me to create well-being, then why not?

Here’s my reason for restarting a blog. In addition to serving as a tool for organizing and sharing ideas (an end), when I write, I enter a state of flux where time loses its dimensional rigor (a means). So, in a way, it’s therapy. Or maybe a meditation. Either way, here’s something worth trying, even if it becomes yet another project that won’t last long.

Writing something is better than writing nothing.

Actually, it exists and it’s called Modafinil. Another cheaper and more accessible drug, experts say, is called Dropyourphonil, which hurts more than a pinprick. ↩︎